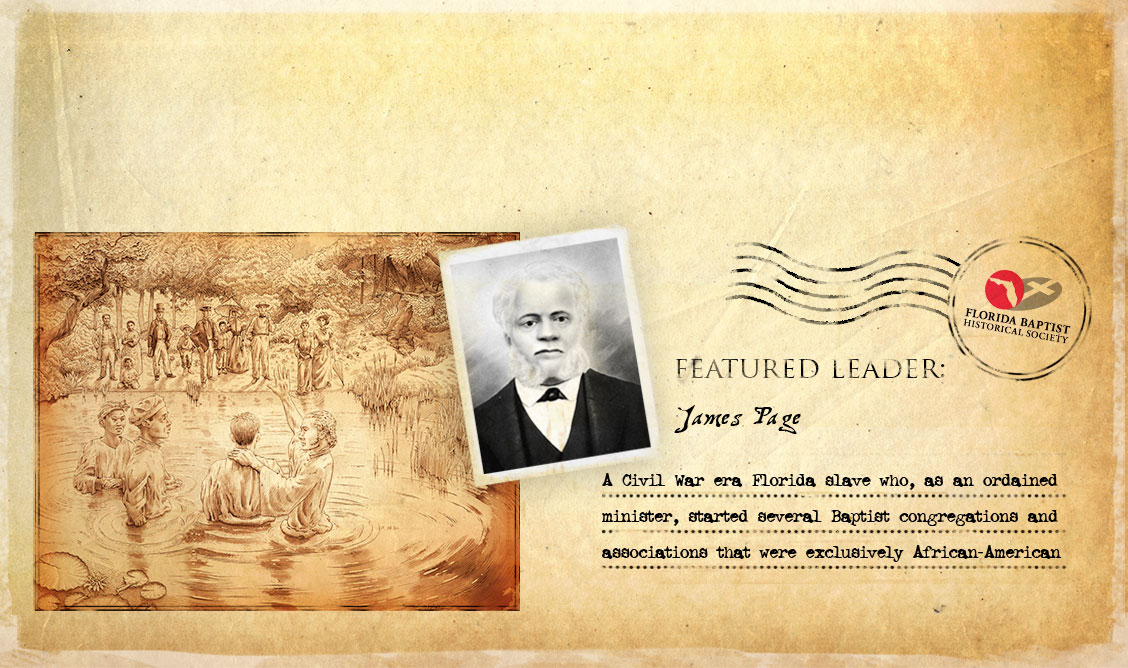

James Page

James Page (1808 – 1883) was an African-descendent slave in middle Florida during the mid-Nineteenth Century who became a missionary Baptist preacher and who developed into one of Florida’s most influential religious leaders of his day. However, this recognition was achieved only after nearly three decades of effectively serving as a bond servant and minister helping other slaves cope with their forced servitude.

Born in Richmond, Virginia, on August 13, 1808, James Page’s mother was a slave owned by John H. Parkhill. Page’s father had been a free man, who was drowned while attempting to go ashore in Liberia during a colonization movement. Little more is known about James Page’s early life other than he married another slave named Elizabeth sometime before 1828.

John Parkhill, along with his family and contingent of slaves, migrated to Leon County, Florida. There he acquired land south of Tallahassee that Parkhill developed into a farm plantation called Bel Air. This site became the permanent home for James and Elizabeth Page.

James Page was greatly influenced by the spirit of God moving in his life. As a result of religious instruction provided by Parkhill, who was an elder in the Presbyterian Church, James Page made a profession of faith in Jesus Christ. Unfortunately at the time, Presbyterian Church tradition did not permit African-descendent persons to join the church. As a consequence, Page sought membership in a missionary Baptist church, which permitted membership and encouraged him to respond to God’s call to the preaching ministry. In time, Page started an on-going preaching ministry at Bel Air, in which he led the slave community to organize in 1850 the first known uniquely Baptist African-descendent congregation in Florida. It was called the Bethlehem Baptist Church at Bel Air Plantation. John Parkhill reportedly donated a parcel of land on his plantation on which the Bethlehem Church was constructed. And surprisingly, the friends of John Parkhill provided financial assistance to underwrite the church building’s construction, in part for their respect for James Page and “his influence on all their servants.” This recognition of James Page’s pastoral abilities and gospel preaching among the slave community was further endorsed by many leading Anglo citizens. Among these were James E. Broome (Governor-elect of Florida and a founding member of the Tallahassee Baptist Church) and Benjamin F. Whitner, who provided letters of recommendations for James Page’s ordination.

Subsequently, Page was ordained in August, 1851, in an ordination service conducted by a presbytery comprise of Anglo Baptist ministers who assembled at the Newport Baptist Church of St. Luke, Wakulla County. This action would have made Page the second known African-descendent person in Florida to be ordained as a missionary Baptist minister. As noted in Chapter Two, a slave named Austin Smith was licensed and ordained by the Baptist Church in Key West in 1843.

By 1853, Page began conducting prayer services for bond servants inside Tallahassee, while continuing his pastoral responsibilities at Bel Air. [This ministry in Tallahassee would ultimately result in the establishment in 1870 of another uniquely African-descendent congregation called the Bethel Baptist Church.] Page expanded his itinerant ministry by visiting most of the plantations in Leon County at least one Sunday a month.

With the untimely death in 1854 of plantation owner John Parkhill, James Page was designated as the “protector,” business manger and confident of Parkhill’s widow, roles Page would fulfill for the remainder of his life. Probably because of this position of trust, Page was granted a rare freedom of movement experienced by few bond servants in the South. In response to the demand for his ministerial services, James Page was permitted to travel freely throughout middle Florida, and eventually traveled to Key West and as far north as Thomasville, Georgia.

Emancipation for James Page probably did not come any earlier than it did for all of Florida’s slaves. Freedom officially did not come until many years later on May 20, 1865, when Confederate Florida formally surrendered to Union Brigadier General Edward McCook at the state capitol in Tallahassee. And for many slaves full citizen rights were not officially sanctioned until passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which finally outlawed slavery. But until that day, Page continued his steadfast itinerant ministry of proclaiming the gospel of Christ among middle Florida’s plantations’ bond servants.

James Page, who had benefited from a tutorial education provided by John Parkhill, sought to provide educational opportunities for the recently freed slaves. In 1868 he started a school in Bel Air called the Page School Society which was one of the first schools for African-Americans in Florida. The school subsequently closed. However, the educational interests of James Page did not stop there. He helped the predominately African-American Bethlehem Baptist Association #1 establish in 1879 at Live Oak the first African-American Baptist school that did survive. It was first called The Live Oak of Florida Institute, and with the help of the American Baptist Home Mission Board, opened in October 1880. The school was the forerunner of the present Florida Memorial College located in Miami.

Page died in Leon County at the age of 75 years old. Having been actively preaching right up to the week of his death, the Weekly Floridian reported that he died “quietly and peacefully” on March 16, 1883. Page is buried in Tallahassee’s Old City Cemetery.

Primary and Secondary Sources:

Minutes, Florida Baptist Association, 1856, p. 17; and 1860.

Larry E. Rivers, Slavery in Florida, p. 120.

George P McKinney and Richard I. McKinney, History of the Black Baptists of Florida, 1850-1985,

(Miami: Florida Memorial College Press, 1987), p. 23.

Larry E. Rivers, “Baptist Minister James Page,” Florida’s Heritage of Diversity, (Tallahassee:

Sentry Press, 1997), p. 44.

Leslie L. Ashford, “Loyal to the end: the life of James Page 1808-1883.” The Journal of Negro History. Vol. 82, Issue 1, 1997, p.169ff.

Weekly Floridian, March 20, 1883.

By the numbers: Our Baptist historical resources

The Florida Baptist Historical Society maintains an extensive collection of historical resources and conducts historical research.